Being a notorious completionist, when I enjoy a series, I eventually foray into its earliest installments. Partly out of curiosity to see the evolution over the years. Partly to be aware of the overarching story, if there is one. This is how I got around to Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. Having bought the Collector’s Edition for the Gamecube, which included Ocarina of Time, Majora’s Mask and the first two Zelda games, I thought that this was a good occasion for some videogame archaeology. I should’ve known what to expect before even starting. Maybe I don’t have the best reflexes in the world, and maybe I’m just no good at oldschool games, but I still have nightmarish memories of the first opus in the series: unforgivably difficult, no story to speak of, no indications as to the order in which to do things. Well, Zelda II is the same. But worse.

Being a notorious completionist, when I enjoy a series, I eventually foray into its earliest installments. Partly out of curiosity to see the evolution over the years. Partly to be aware of the overarching story, if there is one. This is how I got around to Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. Having bought the Collector’s Edition for the Gamecube, which included Ocarina of Time, Majora’s Mask and the first two Zelda games, I thought that this was a good occasion for some videogame archaeology. I should’ve known what to expect before even starting. Maybe I don’t have the best reflexes in the world, and maybe I’m just no good at oldschool games, but I still have nightmarish memories of the first opus in the series: unforgivably difficult, no story to speak of, no indications as to the order in which to do things. Well, Zelda II is the same. But worse.

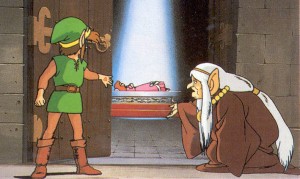

In terms of storyline, it’s a direct sequel to the first game (one of the rare instances of such continuity within the series). This doesn’t really amount to much, however, since it takes place several years later. Link is older, and Zelda isn’t the same one as in the first game, but rather an ancestor, asleep in a remote chamber of Hyrule Castle under the effects of a spell cast by a long-dead magician (and all of the princesses in the royal family have been named in her honour since then). So they may just as well have been different characters altogether. Just like in most of the other games in the series. Anyway, Link discovers a mark on his hand, indicating that he is meant to wield the Triforce of Courage, which is located in the Great Palace and can supposedly break the curse on the sleeping Zelda. To unlock the way to this palace, he is given six crystals to place in six other palaces around Hyrule, which should open the way to the Great Palace. Along the way, he needs to avoid getting killed by followers of Ganon, who seek to resurrect him by sprinkling Link’s blood on his ashes. Nice. This does mean, however, that this is one of the very few games in the series where you don’t actually fight Ganon.

In terms of storyline, it’s a direct sequel to the first game (one of the rare instances of such continuity within the series). This doesn’t really amount to much, however, since it takes place several years later. Link is older, and Zelda isn’t the same one as in the first game, but rather an ancestor, asleep in a remote chamber of Hyrule Castle under the effects of a spell cast by a long-dead magician (and all of the princesses in the royal family have been named in her honour since then). So they may just as well have been different characters altogether. Just like in most of the other games in the series. Anyway, Link discovers a mark on his hand, indicating that he is meant to wield the Triforce of Courage, which is located in the Great Palace and can supposedly break the curse on the sleeping Zelda. To unlock the way to this palace, he is given six crystals to place in six other palaces around Hyrule, which should open the way to the Great Palace. Along the way, he needs to avoid getting killed by followers of Ganon, who seek to resurrect him by sprinkling Link’s blood on his ashes. Nice. This does mean, however, that this is one of the very few games in the series where you don’t actually fight Ganon.

As for the gameplay, picture a hybrid between an old Super Mario game and an RPG. And no, you don’t get Legend of the Seven Stars (if only!), but rather some kind of unholy offspring. It comes as no surprise that this system has never been reused in the series since. There’s an overworld map, peppered with dungeons and visible enemies. Running into one of them or entering a dungeon plonks Link into a sidescrolling environment. He gets three lives and gains experience points in battle. Pretty bizarre for a Zelda game, but that’s not a problem in itself. If Link loses a life, he restarts at the entrance to the area. But god forbid you should actually get a Game Over (ie. lose all three of Link’s lives). Because that takes him back to the first area of the game. Meaning that he’ll have to

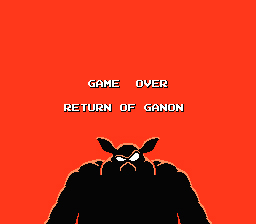

As for the gameplay, picture a hybrid between an old Super Mario game and an RPG. And no, you don’t get Legend of the Seven Stars (if only!), but rather some kind of unholy offspring. It comes as no surprise that this system has never been reused in the series since. There’s an overworld map, peppered with dungeons and visible enemies. Running into one of them or entering a dungeon plonks Link into a sidescrolling environment. He gets three lives and gains experience points in battle. Pretty bizarre for a Zelda game, but that’s not a problem in itself. If Link loses a life, he restarts at the entrance to the area. But god forbid you should actually get a Game Over (ie. lose all three of Link’s lives). Because that takes him back to the first area of the game. Meaning that he’ll have to  trek all the way to where he was before dying. I’ll just let you imagine how that feels when you’re nearing the end of the game. And three lives whisk by very quickly. Especially since there’s no permanent way to obtain more; every time you get a Game Over, you’re brought back to three. Of course, there’s the slight additional problem that getting a Game Over is the only way to save. Yeap.

trek all the way to where he was before dying. I’ll just let you imagine how that feels when you’re nearing the end of the game. And three lives whisk by very quickly. Especially since there’s no permanent way to obtain more; every time you get a Game Over, you’re brought back to three. Of course, there’s the slight additional problem that getting a Game Over is the only way to save. Yeap.

So you’d think that avoiding a Game Over would be a good idea. That would be underestimating the combat system. Forget about steep learning curves. Or even 90° ones. In this game, the learning curve forms an acute angle. I actually had to give up trying to play it on my Gamecube and resort to a NES emulator. So I could, y’know, save. Otherwise, I’d still be trying to finish the first dungeon. And I really wish I was kidding. Not only are there very limited ways of recovering Link’s HP and magic power in the field (a handful of potions can be found or dropped after a battle), but the enemies are brutally unforgiving. Especially Iron

So you’d think that avoiding a Game Over would be a good idea. That would be underestimating the combat system. Forget about steep learning curves. Or even 90° ones. In this game, the learning curve forms an acute angle. I actually had to give up trying to play it on my Gamecube and resort to a NES emulator. So I could, y’know, save. Otherwise, I’d still be trying to finish the first dungeon. And I really wish I was kidding. Not only are there very limited ways of recovering Link’s HP and magic power in the field (a handful of potions can be found or dropped after a battle), but the enemies are brutally unforgiving. Especially Iron  Knuckles, who have mind-bogglingly amazing AI for a NES game. If you thought they were hard in any of the subsequent Zelda games, you’ve got another one coming. The blue ones are particularly bad. They continuously chuck swords, of which they have an infinite supply. This is probably the closest thing to actual Sword-Chucks that you’ll find outside of 8-Bit Theater. It also looks profoundly dodgy when they switch to leg strikes.

Knuckles, who have mind-bogglingly amazing AI for a NES game. If you thought they were hard in any of the subsequent Zelda games, you’ve got another one coming. The blue ones are particularly bad. They continuously chuck swords, of which they have an infinite supply. This is probably the closest thing to actual Sword-Chucks that you’ll find outside of 8-Bit Theater. It also looks profoundly dodgy when they switch to leg strikes.

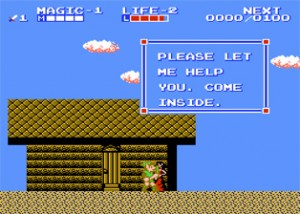

To compensate for the hair-tearing difficulty, the game offers a few chuckles at its own expense. Link–who is an adult in this game (another rare instance in the series)–allows himself some GTA-like escapades, as if the game were having a bizarre premonitory, cross-genre flash. Every town has a woman in a red dress walking around in front of a house. If Link talks to her, she invites him to come in. And then, all you see is his life bar filling up. Hey, even 8-bit studs need their action. However, this becomes a lot more disturbing when it comes to recovering magic power. The method is exactly the same, but Link has to talk to a little granny instead…who then gives him her ‘special medicine’.

To compensate for the hair-tearing difficulty, the game offers a few chuckles at its own expense. Link–who is an adult in this game (another rare instance in the series)–allows himself some GTA-like escapades, as if the game were having a bizarre premonitory, cross-genre flash. Every town has a woman in a red dress walking around in front of a house. If Link talks to her, she invites him to come in. And then, all you see is his life bar filling up. Hey, even 8-bit studs need their action. However, this becomes a lot more disturbing when it comes to recovering magic power. The method is exactly the same, but Link has to talk to a little granny instead…who then gives him her ‘special medicine’.

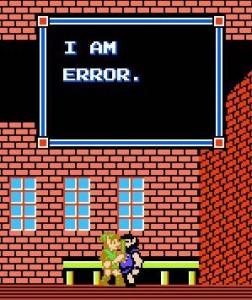

Among other laughable details, there’s the translation, featuring such timeless classics as the “N°3 TRIFORCE”. Or “I AM ERROR”, one of the unforgettable–and oddly philosophical, when you think about it–responses Link will get during his sometimes baffling encounters with the denizens of the game. Or the Spell spell. Talk about stating the obvious. Or does Link have orthography problems? There’s also the aptly named Fairy spell, which is used to fly over obstacles. It transforms Link into one of those cute lil’ fairies that are commonly used to replenish health in Zelda games, complete with a red dress and a little crown. So not only does it shrink him and allow him to fly, but he also gets a sex change thrown in. It’s got to be one of the most impressive magic spells I’ve ever encountered. I’m sure Tingle, the incredibly creepy fairy guy from Majora’s Mask, would’ve loved the concept.

Among other laughable details, there’s the translation, featuring such timeless classics as the “N°3 TRIFORCE”. Or “I AM ERROR”, one of the unforgettable–and oddly philosophical, when you think about it–responses Link will get during his sometimes baffling encounters with the denizens of the game. Or the Spell spell. Talk about stating the obvious. Or does Link have orthography problems? There’s also the aptly named Fairy spell, which is used to fly over obstacles. It transforms Link into one of those cute lil’ fairies that are commonly used to replenish health in Zelda games, complete with a red dress and a little crown. So not only does it shrink him and allow him to fly, but he also gets a sex change thrown in. It’s got to be one of the most impressive magic spells I’ve ever encountered. I’m sure Tingle, the incredibly creepy fairy guy from Majora’s Mask, would’ve loved the concept.

In conclusion, if you’re ever tempted, for some unfathomable reason, to try this game out, just pray you can get through it without terminal finger cramps. And never look back. Thank god that Zelda has evolved since then. That’s probably the one good thing I got out of this experience: a better appreciation of the more recent Zelda opuses. Nostalgia is all well and good, but you gotta be realistic sometimes: not everything was better back in Ye Olde Days.

In conclusion, if you’re ever tempted, for some unfathomable reason, to try this game out, just pray you can get through it without terminal finger cramps. And never look back. Thank god that Zelda has evolved since then. That’s probably the one good thing I got out of this experience: a better appreciation of the more recent Zelda opuses. Nostalgia is all well and good, but you gotta be realistic sometimes: not everything was better back in Ye Olde Days.