The culprit: Portal 2 (PC, Mac, PlayStation3, Xbox 360)

A good sequel is always a pleasant surprise. But a good sequel to a sleeper hit is a special kind of treat. The first Portal was a flash of wickedly funny genius out of left field. Portal 2 confirms that the series is in the hands of consistently brilliant writers. In other words, the cake wasn’t a lie.

A good sequel is always a pleasant surprise. But a good sequel to a sleeper hit is a special kind of treat. The first Portal was a flash of wickedly funny genius out of left field. Portal 2 confirms that the series is in the hands of consistently brilliant writers. In other words, the cake wasn’t a lie.

By now, the qualities of the first game have been widely broadcast, but, shocking as it may seem, it did also have flaws, the most notable of which was repetitiveness. While its length successfully prevented that from becoming a major problem (at least on first playthrough), more of the same for a whole second game would’ve been problematic. Well, Portal 2 avoids that problem, and, in retrospect, makes the first game feel like a bit of a prototype. Which, to be entirely fair, it was.

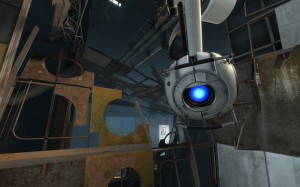

You are still in control of Chell (with a mysterious wardrobe upgrade), whom, as you may remember, the first game left in rather dire straits. Now, she is awakened in a stasis room–or Extended Relaxation Centre–by a voice on the intercom for a short tutorial: the controls are pretty much the same as before: walk, jump, crouch, pick up stuff and, later, place portals. She’s then put back to sleep; when she next awakens, several years–or decades?–have obviously passed (c.f. the pillow). An autonomous, rather worried-sounding personality core named Wheatley contacts her and helps her escape, as she has apparently been scheduled to be terminated. This leads to two discoveries: one, the Aperture Science facility is huge; two, it’s now in a rather poor state.

You are still in control of Chell (with a mysterious wardrobe upgrade), whom, as you may remember, the first game left in rather dire straits. Now, she is awakened in a stasis room–or Extended Relaxation Centre–by a voice on the intercom for a short tutorial: the controls are pretty much the same as before: walk, jump, crouch, pick up stuff and, later, place portals. She’s then put back to sleep; when she next awakens, several years–or decades?–have obviously passed (c.f. the pillow). An autonomous, rather worried-sounding personality core named Wheatley contacts her and helps her escape, as she has apparently been scheduled to be terminated. This leads to two discoveries: one, the Aperture Science facility is huge; two, it’s now in a rather poor state.

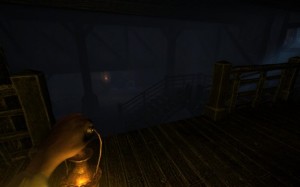

Thus, instead of the pristine white rooms of the first game, Chell now travels through dilapidated, half-overgrown environments, once again with the goal to save her skin. This gives the game a more chaotic feel. You now have to get even more creative with the rules, and the puzzles still provide just the right level of challenge, between figuring out the solutions and executing them.

Thus, instead of the pristine white rooms of the first game, Chell now travels through dilapidated, half-overgrown environments, once again with the goal to save her skin. This gives the game a more chaotic feel. You now have to get even more creative with the rules, and the puzzles still provide just the right level of challenge, between figuring out the solutions and executing them.

Chell still has a portal gun, since that is, after all, the founding principle of the series, but many new gadgets are also introduced, such as Aerial Faith Plates (boing!), Hard Light Bridges and Excursion Funnels (i.e. tractor beams). Weighted Storage Cubes (and the Companion Cube <3) also make a comeback, now joined by their cousins, the Redirection Cubes. Of course, the game would feel incomplete without the good ol’ turrets, which now come in startlingly humorous varieties, including an Oracle Turret. They’re still just as deadly though–well, mostly–, but the game’s autosave function will take care of any accidental demises.

Chell still has a portal gun, since that is, after all, the founding principle of the series, but many new gadgets are also introduced, such as Aerial Faith Plates (boing!), Hard Light Bridges and Excursion Funnels (i.e. tractor beams). Weighted Storage Cubes (and the Companion Cube <3) also make a comeback, now joined by their cousins, the Redirection Cubes. Of course, the game would feel incomplete without the good ol’ turrets, which now come in startlingly humorous varieties, including an Oracle Turret. They’re still just as deadly though–well, mostly–, but the game’s autosave function will take care of any accidental demises.

Wheatley accompanies and helps Chell, much as GLaDOS did in the first game, with the difference that he is mobile and visible. A lot of people seem to dislike him, and I can see where they’re coming from: he’s very different from GLaDOS, a bumbling, manic worrywart instead of a cool, cynical mastermind. Still, I enjoyed the change of pace, and there’s more to him than first meets the eye.

Wheatley accompanies and helps Chell, much as GLaDOS did in the first game, with the difference that he is mobile and visible. A lot of people seem to dislike him, and I can see where they’re coming from: he’s very different from GLaDOS, a bumbling, manic worrywart instead of a cool, cynical mastermind. Still, I enjoyed the change of pace, and there’s more to him than first meets the eye.

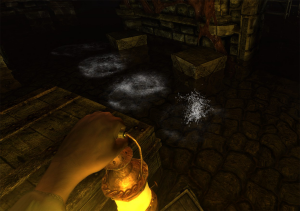

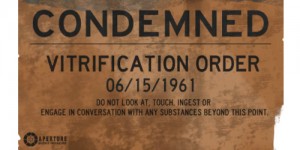

Apart from what’s left of the main facility, which notably features some brilliant safety advertisements for Aperture employees, such as the ‘Animal King Takeover’, Chell also gets to explore the underbelly of Aperture, as she visits the ruins of its old premises, located in a salt mine. How and why she gets there is up to you to discover, but predictable it certainly is not. These levels are slightly harder, as the state of the infrastructure makes them more dangerous to navigate, and the devices used back in the day were different from the ones you may be accustomed to. Chell gets to sample old test chamber prototypes, but also gadgets that were abandoned as the facility developed, such as gels, which you’ll find shooting out of pipes and can direct on various surfaces at your convenience.

Apart from what’s left of the main facility, which notably features some brilliant safety advertisements for Aperture employees, such as the ‘Animal King Takeover’, Chell also gets to explore the underbelly of Aperture, as she visits the ruins of its old premises, located in a salt mine. How and why she gets there is up to you to discover, but predictable it certainly is not. These levels are slightly harder, as the state of the infrastructure makes them more dangerous to navigate, and the devices used back in the day were different from the ones you may be accustomed to. Chell gets to sample old test chamber prototypes, but also gadgets that were abandoned as the facility developed, such as gels, which you’ll find shooting out of pipes and can direct on various surfaces at your convenience.

Blue (repulsion) gel allows Chell to bounce very high; orange (propulsion) gel allows her to go into Speedy Gonzales mode; and white (conversion) gel allows her to coat surfaces in white paint, thereby enabling the placement of portals in previously inaccessible locations. Some people may find the gels rather haphazard as a means of puzzle solving, but I thought that that was the whole point: they were discontinued as a product, after all, there’s gotta be a reason for that. Overall, I found this a welcome diversion from ‘normal’ portal mechanics and a way to keep the player interested and constantly on their toes.

Blue (repulsion) gel allows Chell to bounce very high; orange (propulsion) gel allows her to go into Speedy Gonzales mode; and white (conversion) gel allows her to coat surfaces in white paint, thereby enabling the placement of portals in previously inaccessible locations. Some people may find the gels rather haphazard as a means of puzzle solving, but I thought that that was the whole point: they were discontinued as a product, after all, there’s gotta be a reason for that. Overall, I found this a welcome diversion from ‘normal’ portal mechanics and a way to keep the player interested and constantly on their toes.

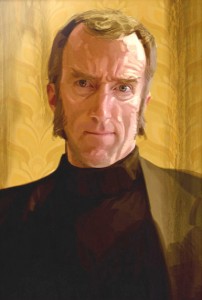

The Old Aperture levels also serve to introduce, via recordings, the now-defunct but legendary Cave Johnson, founder of the company, champion of scientific progress (well, sorta…) and author of truly epic speeches, such as the one about combustible lemons, which I will let you savour firsthand. It also creates a much-enhanced backstory for the game, something that was markedly absent from the first opus. It successfully builds on the already present theme of science gone haywire, and I found that it brought welcome depth and context to the table, as well as some startling revelations. It’s also at this point that you will have to deal with a very special potato battery.

The Old Aperture levels also serve to introduce, via recordings, the now-defunct but legendary Cave Johnson, founder of the company, champion of scientific progress (well, sorta…) and author of truly epic speeches, such as the one about combustible lemons, which I will let you savour firsthand. It also creates a much-enhanced backstory for the game, something that was markedly absent from the first opus. It successfully builds on the already present theme of science gone haywire, and I found that it brought welcome depth and context to the table, as well as some startling revelations. It’s also at this point that you will have to deal with a very special potato battery.

I feel I should also mention the ending of the game, which manages to be hilarious, completely crazy and emotional at the same time. Spoilers are out of the question, of course, but, just to give you an idea, the description of the achievement you receive for experiencing it reads “That just happened.” I must also put in a word for the Space Personality Core. You’ll know why when you encounter it.

I feel I should also mention the ending of the game, which manages to be hilarious, completely crazy and emotional at the same time. Spoilers are out of the question, of course, but, just to give you an idea, the description of the achievement you receive for experiencing it reads “That just happened.” I must also put in a word for the Space Personality Core. You’ll know why when you encounter it.

Portal 2 introduces a two-player mode instead of the challenge rooms of its predecessor. Each player is put in control of a robot and tasked with testing out experimental chambers. Since they are robots, they are in no danger of dying, which makes them perfect for the job and is precisely the reason why they were created for testing. There’s a squat, rotund ‘male’ robot with a blue eye called Atlas and a tall, oblong ‘female’ one with a yellow eye called P-Body: they even made it onto the game’s cover, which, admittedly, is a bit misleading, because they barely appear in the main game, and you never control them. Be that as it may, in two-player mode, each has a portal gun, which allows players to work with four portals instead of two and thus greatly expands the scope of what they can do. Again, as with all multiplayer modes, I’ve not touched it, so I can’t really give an opinion on it. However, I’ve heard a lot of praise for it, and I have to admit that the robots are cute, at least, and that the Portal universe lends itself to this kind of gameplay pretty much ideally.

Portal 2 introduces a two-player mode instead of the challenge rooms of its predecessor. Each player is put in control of a robot and tasked with testing out experimental chambers. Since they are robots, they are in no danger of dying, which makes them perfect for the job and is precisely the reason why they were created for testing. There’s a squat, rotund ‘male’ robot with a blue eye called Atlas and a tall, oblong ‘female’ one with a yellow eye called P-Body: they even made it onto the game’s cover, which, admittedly, is a bit misleading, because they barely appear in the main game, and you never control them. Be that as it may, in two-player mode, each has a portal gun, which allows players to work with four portals instead of two and thus greatly expands the scope of what they can do. Again, as with all multiplayer modes, I’ve not touched it, so I can’t really give an opinion on it. However, I’ve heard a lot of praise for it, and I have to admit that the robots are cute, at least, and that the Portal universe lends itself to this kind of gameplay pretty much ideally.

Overall, I thought Portal 2 was an excellent follow up to its predecessor, expanding on the original story in all the good ways and creating a wonderfully exhilarating, fun experience, filled with humour, surprises and even more gravity-defying stunts. Of course, there will always be things to criticise, and complaints have included a lack of direction in the second act of the game or the length of loading times. None of that bothered me, however; I had a genuine blast and, to anyone who hasn’t played this yet, I put the following question: “what are you waiting for?”

Overall, I thought Portal 2 was an excellent follow up to its predecessor, expanding on the original story in all the good ways and creating a wonderfully exhilarating, fun experience, filled with humour, surprises and even more gravity-defying stunts. Of course, there will always be things to criticise, and complaints have included a lack of direction in the second act of the game or the length of loading times. None of that bothered me, however; I had a genuine blast and, to anyone who hasn’t played this yet, I put the following question: “what are you waiting for?”