What if you had made a terrible mistake? And what if you could manipulate time to rectify it? No, this isn’t Prince of Persia, but Braid, one of the most famous and critically acclaimed download-exclusive indie games to date. Initially available on XBLA, it has since found its way onto other platforms, thus becoming available to a wider audience. As such things often go, at first glance, it appears to be a simple platformer with a  childish design and storyline. But if the game’s cover art, depicting a broken hourglass and a crumbling castle made from the spilled sand wasn’t indication enough, playing the actual game quickly reveals that there is more to it than meets the eye. Not only does it display treasures of ingenuity, but its plot also wanders off into distinctly non-childish territory, both wistful and ponderous. All in all, this is still one of the cleverest, most interesting games I have played, and I heartily recommend it.

childish design and storyline. But if the game’s cover art, depicting a broken hourglass and a crumbling castle made from the spilled sand wasn’t indication enough, playing the actual game quickly reveals that there is more to it than meets the eye. Not only does it display treasures of ingenuity, but its plot also wanders off into distinctly non-childish territory, both wistful and ponderous. All in all, this is still one of the cleverest, most interesting games I have played, and I heartily recommend it.

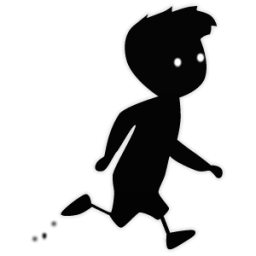

The game’s protagonist is Tim, a little red-haired fellow in a suit and tie who is trying to rescue a princess. If you did a double-take at the “suit and tie” part, you’d be on to something. The narrative, which consists of Tim’s memories and is presented in the form of short introductory texts before each of the game’s levels, is ambiguous on what the exact relationship between them was, but Tim appears to have made some kind of mistake which resulted in the loss of the princess, and would now like nothing more than to rectify it. This is all very vague, and, on a certain level, remains that way, were it not for several small clues interspersed within the texts which hint at a different kind of story behind Tim’s apparently disjointed musings and his strange quest.

game’s protagonist is Tim, a little red-haired fellow in a suit and tie who is trying to rescue a princess. If you did a double-take at the “suit and tie” part, you’d be on to something. The narrative, which consists of Tim’s memories and is presented in the form of short introductory texts before each of the game’s levels, is ambiguous on what the exact relationship between them was, but Tim appears to have made some kind of mistake which resulted in the loss of the princess, and would now like nothing more than to rectify it. This is all very vague, and, on a certain level, remains that way, were it not for several small clues interspersed within the texts which hint at a different kind of story behind Tim’s apparently disjointed musings and his strange quest.

The gameplay revolves around manipulating time by various means to defeat enemies and solve puzzles, some of which are deliciously tricky and require the ability to think outside the box, as well as a good grasp of the game’s mechanics. Tim first appears  against an ominous backdrop of a burning city to eventually reach a quiet, night-time street and a house, which serves as the game’s hub. It contains six rooms, each with an empty picture frame and a door which leads to one of the game’s six levels. Each one of those is subdivided into several sub-levels, which contain puzzle pieces that Tim must collect, to then complete each picture frame. The last level is located in the attic and can only be reached by a ladder which gradually gains new segments as Tim clears the other levels.

against an ominous backdrop of a burning city to eventually reach a quiet, night-time street and a house, which serves as the game’s hub. It contains six rooms, each with an empty picture frame and a door which leads to one of the game’s six levels. Each one of those is subdivided into several sub-levels, which contain puzzle pieces that Tim must collect, to then complete each picture frame. The last level is located in the attic and can only be reached by a ladder which gradually gains new segments as Tim clears the other levels.

Each level features a different time-related mechanic, which is reflected in its name. The first (which is actually number 2; you’ll understand why later on), called “Time and Forgiveness”, introduces the concept of rewinding time if Tim makes a mistake or plummets to his death, although you can also fast forward it when required. The second level is named “Time and Mystery” and introduces objects, outlined in sparkly green, which are unaffected by temporal manipulation (e.g. if Tim activates a green lever, it will remain activated even if he rewinds). These objects also reappear in later levels. “Time and Place”, the third level, links time to Tim’s movements: if he moves to the right, time moves forward, if he moves to the left, it  moves backwards. The fourth level, “Time and Decision”, introduces objects outlined in purple: whenever Tim rewinds time, his shadow will proceed to repeat his actions prior to the rewind and will be able to interact with the aforementioned purple objects. This effectively allows him to perform multiple actions at the same time. The fifth level, “Hesitance”, introduces a ring which, when dropped, will create a time-slowing bubble around itself: objects nearer to the centre of the bubble will move slower than objects nearer its perimeter. Finally, in the last level, simply titled “1”, time continuously flows backwards (meaning that rewinding makes it flow normally).

moves backwards. The fourth level, “Time and Decision”, introduces objects outlined in purple: whenever Tim rewinds time, his shadow will proceed to repeat his actions prior to the rewind and will be able to interact with the aforementioned purple objects. This effectively allows him to perform multiple actions at the same time. The fifth level, “Hesitance”, introduces a ring which, when dropped, will create a time-slowing bubble around itself: objects nearer to the centre of the bubble will move slower than objects nearer its perimeter. Finally, in the last level, simply titled “1”, time continuously flows backwards (meaning that rewinding makes it flow normally).

Visually and aurally, the game is enchanting. Each level has its own atmosphere and beautifully rendered, vibrantly coloured, environments and backgrounds, which are somewhat reminiscent of Van Gogh paintings. Each also has its own lovely musical theme, but both look and sound take a distinctly more sombre turn once you reach the final levels. This is also the second major clue as to the game’s most widely accepted interpretation. From then on, it’s very much a ‘so that’s what it was’ process.

Visually and aurally, the game is enchanting. Each level has its own atmosphere and beautifully rendered, vibrantly coloured, environments and backgrounds, which are somewhat reminiscent of Van Gogh paintings. Each also has its own lovely musical theme, but both look and sound take a distinctly more sombre turn once you reach the final levels. This is also the second major clue as to the game’s most widely accepted interpretation. From then on, it’s very much a ‘so that’s what it was’ process.

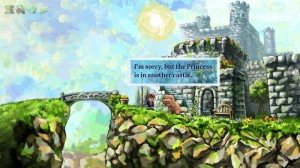

The game also contains some humorous references, including numerous callbacks to Super Mario Bros.: not only do the most common enemies in the game resemble goombas and piranha plants (and the former can be defeated by stomping on them), but the final sub-level of each level contains a small fortress with a flag, which rises as Tim reaches it, as well as a small,

The game also contains some humorous references, including numerous callbacks to Super Mario Bros.: not only do the most common enemies in the game resemble goombas and piranha plants (and the former can be defeated by stomping on them), but the final sub-level of each level contains a small fortress with a flag, which rises as Tim reaches it, as well as a small,  plushy-looking dinosaur which informs him that the princess is in another castle. Apart from that, another commonly-encountered enemy in the game is almost a dead ringer for the killer rabbit from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. In fact, I’m starting to wonder whether Tim’s name isn’t another reference to that film…

plushy-looking dinosaur which informs him that the princess is in another castle. Apart from that, another commonly-encountered enemy in the game is almost a dead ringer for the killer rabbit from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. In fact, I’m starting to wonder whether Tim’s name isn’t another reference to that film…

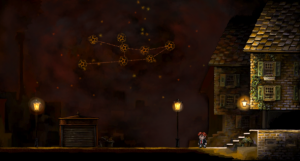

Somewhat uncommonly by download-exclusive game standards, Braid has also put some real effort into optional goals. Some of the game’s levels contain hidden areas, accessing which rewards Tim with a star (yet another Super Mario Bros. reference). There are eight stars in total; one of them can be missed if you complete the picture-frame puzzle for the corresponding level before obtaining it, and another one requires obtaining an alternate ending for the game (which isn’t as satisfying as the normal one).  Each new star is added to the Andromeda constellation, which hangs above the entrance to the house in the hub level. Tim can look up at it to check his progress, and once all stars have been collected, it will slightly change its appearance, all in coherence with the game’s themes. And if that wasn’t enough, when you’ve finished the game once, a speedrun mode becomes available, netting you an achievement if you manage to complete one in less than 45 minutes.

Each new star is added to the Andromeda constellation, which hangs above the entrance to the house in the hub level. Tim can look up at it to check his progress, and once all stars have been collected, it will slightly change its appearance, all in coherence with the game’s themes. And if that wasn’t enough, when you’ve finished the game once, a speedrun mode becomes available, netting you an achievement if you manage to complete one in less than 45 minutes.

There are very few genuine gripes I have with Braid. The major one would probably be the fact the game autosaves your progress, but does so on a single save file. Meaning that, should you fail to obtain the aforementioned missable star, for example, you would have to restart a brand new game to do so. It also means that the speedrun must be achieved in a single sitting and that, should you make a major mistake somewhere, say, in level six, you’d have to restart all the way from the beginning as well. I don’t think I need to tell you how aggravating that can be. Another gripe would be that another one of the stars takes an unnecessarily long amount of time (almost two hours simply waiting!) to obtain. Some people have also complained that the game was too short. Obviously, when you’ve cleared it once and are practicing for a speedrun, it may,  indeed, seem like it whisks by in no time. Although, if it’s your first playthrough, and you’re racking your brain to figure out a puzzle, but also taking time to admire the artwork and music, chances are you won’t have that impression. Bottom line: do give this little gem a try, it’s well worth it.

indeed, seem like it whisks by in no time. Although, if it’s your first playthrough, and you’re racking your brain to figure out a puzzle, but also taking time to admire the artwork and music, chances are you won’t have that impression. Bottom line: do give this little gem a try, it’s well worth it.